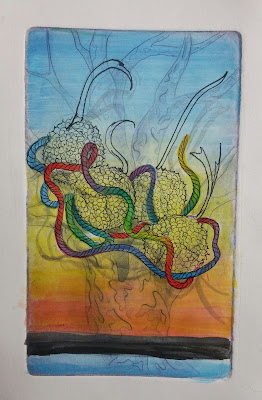

Last week I talked about the color fields that I incorporated into my prints. Today we'll take a look at the still life element that I decided to integrate into them.

Between April and May of 2014 I did a series of twelve studies involving sycamore seed balls and leftover multicolored yarn from a scarf a friend had knitted for me. I had picked up the seed balls during my walks home from work; they were from the sycamore I pass under on Pennsylvania Avenue. I don't remember anymore whether I had specifically wanted to pair the seed balls with the yarn, or whether it happened accidentally. All I know is that they ended up together, and that I liked the arrangement so well that I drew it.

As satisfying as these prints were, however, they did not use the original twelve sketches, and while I had abandoned my first project attempt, I still felt compelled to use them. When I was sketching out this latest print, project then, with its emphasis on my local surroundings, I discovered a way to revive my sketches and bring them to fruition. I made twelve impressions, painted twelve color fields, and now prepared to recreate twelve drawings.

For the yarn, I used acrylic gesso, as I wanted this to be opaque, allowing the colors to stand out.

I then added the shadows cast by the yarn and seeds balls in ink washes.

Next week we'll wrap up this series by look at the complete body of works.

Between April and May of 2014 I did a series of twelve studies involving sycamore seed balls and leftover multicolored yarn from a scarf a friend had knitted for me. I had picked up the seed balls during my walks home from work; they were from the sycamore I pass under on Pennsylvania Avenue. I don't remember anymore whether I had specifically wanted to pair the seed balls with the yarn, or whether it happened accidentally. All I know is that they ended up together, and that I liked the arrangement so well that I drew it.

While I always enjoy sketching, there was a particular quality about this still life that intrigued me. Sure, I liked the contrasting colors and textures, and there was enough detail to keep my attention, but what really interested was the potential for composition. With four seed balls and some yarn, I could create a nearly infinite number of compositions, all by simply changing their arrangements. It reminded me of the work of J.S. Bach. In his fugues especially, Bach turned his compositions into meditations on musicality itself, with the basic melody of a work being transformed into an endless stream of variations.

|

| Image courtesy of https://www.deutschegrammophon.com/en/cat/4744952 |

Eric Siblin discusses Bach's musicality in The Cello Suites, a book I read some years ago when I was an intern at the Dallas Museum of Art. The DMA has a great lecture series called Arts and Letters Live, and Siblin was one of the guest speakers. I had volunteered as a ticket taker for the event, and read the book ahead of time. By focusing on this group of solo works, Siblin delves into Bach's mastery of theme and variation, and how he's able to create so much diversity while exploring a single instrument. The book and the memory of it has stuck with me ever since, whether I'm playing music myself (I once spent an hour in my apartment playing the same ten or so measures of Bach's sonata in E minor on the piano there because I was fascinated with the key changes incorporated in the arpeggios), or working on a series of drawings or prints. What can I say, the idea of seeking out variety within a group of related works resonates with me.

|

| Image courtesy of https://www.amazon.com/Cello-Suites-Casals-Baroque-Masterpiece/dp/0802145248 |

And so, with this book and my own musical experiences in mind, I drew my own theme and variations on my sycamore seeds and yarn. Over the next two weeks, I created and sketched twelve different compositions. I picked twelve because I've always liked that number. It corresponds to the months of the year, and can be divided into several pleasing clusters, whether it's two group of six, three groups of four, or vice-versa.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I'd attempted a larger project with these sketches before. In that first iteration, I focused on the mathematical qualities of the composition. Sometimes I thought of them as musical notes. At one point I even assigned the seeds balls different geometric shapes, as you can see in the corners of these drawings. Ultimately, however, the project fizzled out because I had stripped away the sense of place behind these sketches. While they did have strong mathematical qualities that appealed to me, I also liked the drawings because they represented objects that were intimately connected to my daily routines. I had collected those seed balls on my walks to work, had saved that yarn from a friend. By focusing on their general qualities, I had forgotten the specific charms that attracted me to them in the first place. In other words, I had neglected their thing-ness.

Over the years, I did other sketches of yarn and sycamore seeds, and even completed a couple of prints based on them. One example includes this copper drypoint of a single seed ball. Whereas the original twelve sketches were self-contained compositions, this print was more open. The yarn trails off the page, for instance, and the seeds ball itself is now coming apart, the seeds scattering off the plate.

Just last year, I did another print based on a sycamore seeds sketch, this time incorporating a preserved blowfish. This work was a reflection on museums and collecting rather than a meditation on composition, but it was still very grounded in the thingness of the objects.

As satisfying as these prints were, however, they did not use the original twelve sketches, and while I had abandoned my first project attempt, I still felt compelled to use them. When I was sketching out this latest print, project then, with its emphasis on my local surroundings, I discovered a way to revive my sketches and bring them to fruition. I made twelve impressions, painted twelve color fields, and now prepared to recreate twelve drawings.

We'll track the process of making these drawings by following the process of one print, in this instance January.

I began with the sycamore seeds. After sketching the rough circles in charcoal, I used pen and ink to draw in their outlines. I had originally thought about painting them in, but decided to draw instead so that the landscape would remain visible through them.

I then added color to the yarn.

After the color, I added details to the yarn and seeds balls in micronpen. Finally, I added shadows on the seeds and yarn with pen and ink wash, and used gold and silver gel pens to recreate the gilded effects on the original sketches. I don't remember why I added gold and silver detailing to the sketches, but I liked it visually so I included it here.

And here is the finished drawing:

Next week we'll wrap up this series by look at the complete body of works.

Comments

Post a Comment

Questions? Comments? Speak your mind here.